ASNET and Middle Eastern Film(s) Study Group hosted a symposium.

Please find the details in the following.

——————–

【Report】

The symposium “Knowing Asia: Through Egyptian Film 678” was held on Tuesday, January 26th, 2016, in Fukutake Hall at the University of Tokyo. The three-hour-and-a-half long event, attended by approximately 85 people, was hosted by the Network for Education and Research on Asia (ASNET) and the Middle Eastern Film(s) Study Group (MEFS), and was supported by the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia (IASA), the Research & Information Center for Asian Studies (RICAS), and New Century Film Production.

After opening remarks by Professor Yukio Ikemoto (IASA, Vice-Director of ASNET), the film, entitled 678 and directed by Muhammad Diab, was screened. The 98 minutes movie was followed by comments from three scholars who specialize in, respectively, anthropology, English literature, and queer studies.

The symbolic number 678 refers to a public bus route in Cairo, Egypt. In the film, we follow the stories of three women from different social classes. Faiza, a city clerk, suffers from frequent sexual harassment while riding the 678 bus to work. Seba, a wealthy artist, is sexually attacked in a soccer stadium while accompanied by her husband. Nelly, a telephone operator, experiences constant verbal sexual abuse at her job; her simmering anger reaches a boiling point after she is grabbed by a strange man on the street. She decides to sue the man, for the first time in Egypt, for a sexual offense.

In an introduction, the movie says it is “based on a true story.” It was in 2008 that the first lawsuit against a sexual offense in a public space was brought by a 27-year-old-Egyptian woman. The offender was sentenced to three years in prison. After this incident, laws against sexual offences were added to the Egyptian penal code [Sareh el-Shaarawi 2013]. In an interview, director Diab, who attended the 2008 trial, said he noticed a gap between the genders regarding their perceptions of sexual offenses. He also was surprised by the tendency of other victims to remain silent about their incidents of harassment. In his film, Diab depicts the viewpoints and experiences of both the offenders and the victims, as well as the differences between people within those two groups, in order to shed light on the entire Egyptian social structure behind frequent sexual offences [Murphy 2011].

After the showing of the film, the first of the three commentators at the symposium was Junko Toriyama (a post-doctoral fellow at the Japan Society for the Promotion of the Sciences), who specializes in anthropology and gender studies related to the Middle East. She described the “modern-western” model for male-female relationships, which promotes a balance between marriage, love, and sex (the so-called “romantic love triangle”). She contrasted it with the situation in contemporary Cairo, which has three characteristics: first, love is less valued than the other two components (marriage and sex); second, sexual behavior is regarded as an important manifestation of emotional connections; and third, concealment of sexual objects and behavior in the public sphere (including the concealment of women’s bodies) indicates that the society’s attitudes overemphasize sex. Accordingly, Toriyama commended the film for its accurate depiction of this societal obsession with sex, by placing the stories of the public sexual offences at the forefront against detailed background information.

The next speaker, Noriko Matsunaga (Lecturer at Teikyo University), using her perspective from English literature and feminist theory, gave a feminist reading of 678. The first point the film makes in this context is about how Seba, Faiza, and Nelly, who are from different social backgrounds and would normally never meet, encounter each other at a women’s discussion group that Seba organizes. The members of the group not only talk about sexual offenses but also share their personal experiences and thoughts. Such discussion groups descend from a tradition of feminist activism, called “consciousness raising,” that Matsunaga says was enormously popular in English-speaking countries in the 1960s and 70s.

Second, the film shows that freedom of mobility for women, such as running for exercise outdoors, in Seba’s case, and commuting, in Faiza’s, is also an important issue for feminism; women’s liberation is symbolized in many films by physical mobility. However, 678 does not limit the meaning of mobility to just that of physical movement, but extends it to the issue of violence against women. In so doing, the film broadens our feminist outlook: violence against women is not only sexual and physical, but also, linguistic, moral, and mental, in both individual and social contexts.

Third, the film suggests that feminist activism can best be achieved when it confronts the inequities of social and economic class divisions. We see repeated scenes on the same street where the various characters first encounter each other without knowing it. Because of their different social classes, they would not normally interact with each other, but this changes when their shared experiences of harassment on that street bring them together in Seba’s discussion group. 678 implies that though the street is the venue where violence is performed against the women, it can also be a critical place where people take up feminist activism.

The third symposium speaker, Noritaka Moriyama (Assistant Professor at the University of Tokyo), specializes in queer studies. He said that 678 gave an answer to an important question that scholars and practitioners of feminism have long asked: how can women from various backgrounds be united into a single force? According to Moriyama, it becomes possible through a “transfer of identities” that is depicted in the film. The women transfer between them physical objects and behaviors, such as Seba’s handmade accessories, the act of attacking men, and hair and dress styles. These transfigurations/transformations, on one hand, prevent immediate mutual understanding between the women; the “transfer of identities” makes it difficult for others to tell the women apart, which causes them frustration. On the other hand, by sharing their mutual experiences and feelings, the women began to connect to each other through their imagination. The last scene of the film, in which Faiza compliments Seba’s hairstyle by saying “It looks nice even though I liked the former hairstyle as well,” is a highlight because it shows how the women have achieved a sense of unity.

Moriyama said that both the film and the field of queer studies share an underlying positive attitude toward the transferring of unstable identities. He also complimented the film for its nuanced depiction of the men’s position in the story; the three women neither “relied on” nor “cut off” their relationships with the men around them.

Following the question-and-answer sessions with the commentators, Professor Eiji Nagasawa (member of IASA, RICAS, and advisor at MEFS) gave a closing address. He said, “678 is an excellent piece of work, valuable material for the Area Studies. It is like a food of high nutritional value.”

Reference:

Mekodo Murphy, “Interview: Mohamed Diab” (Mar. 2011) http://www.nytimes.com/video/movies/100000000753112/mohamed-diab.html

Sareh el-Shaarawi, “Egyptian director Mohamed Diab talks about his film on sexual harassment,” (Oct. 2013) http://africasacountry.com/2013/10/egyptian-director-mohamed-diab-talks-about-his-film-on-sexual-harassment/

(Moderator of the symposium/writer of this report: Emi Goto, Associate Professor, ASNET, IASA, and member of MEFS)

——————–

【 Date】

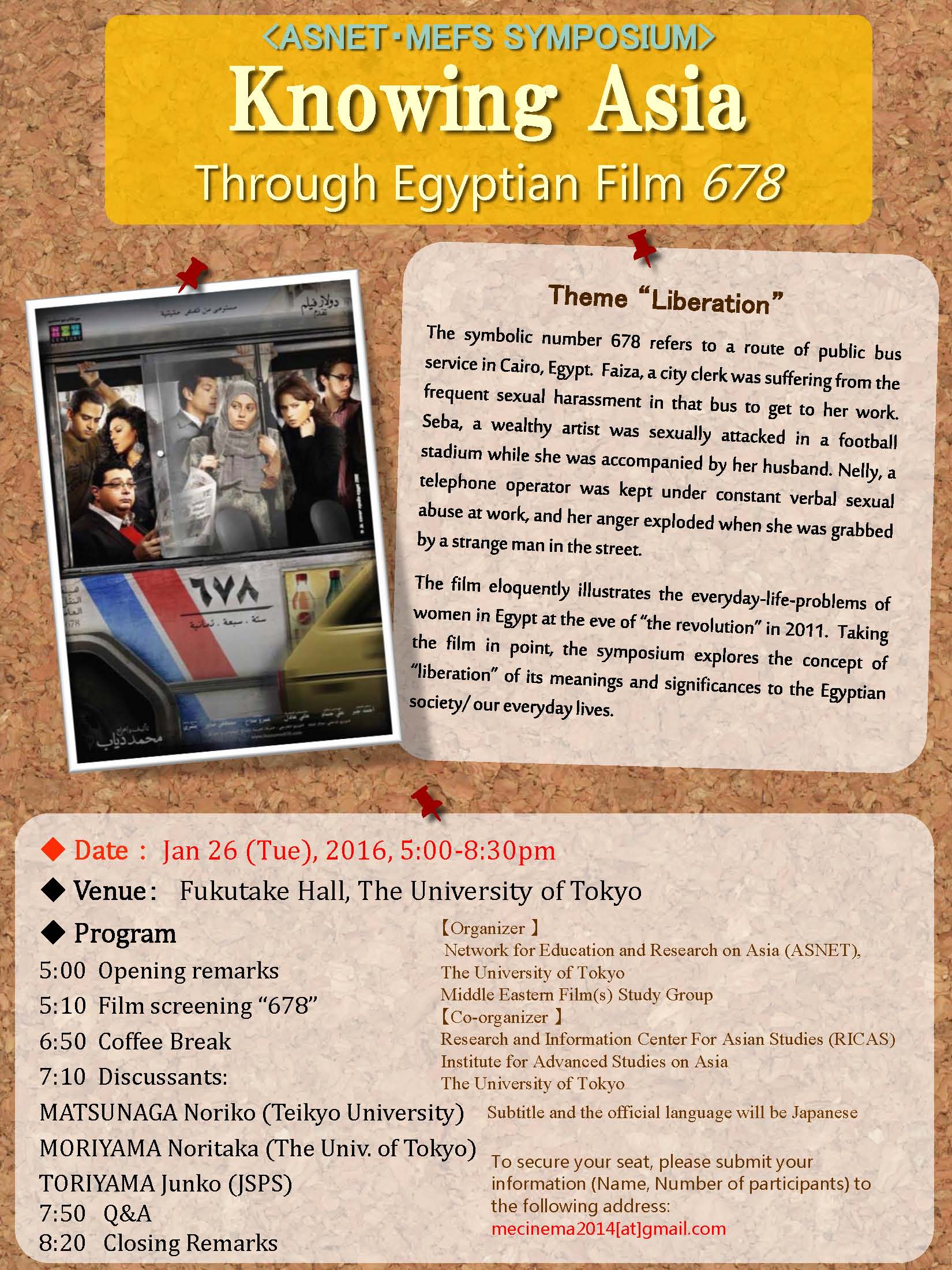

Jan 26 (Tue), 2016, 5:00-8:30pm

【Venue】

Fukutake Hall, The University of Tokyo

http://fukutake.iii.u-tokyo.ac.jp/access/index.html

【Title】

Knowing Asia: Through Egyptian Film 678

【Theme】 Liberation

The symbolic number 678 refers to a route of public bus service in Cairo, Egypt. Faiza, a city clerk was suffering from the frequent sexual harassment in that bus to get to her work. Seba, a wealthy artist was sexually attacked in a football stadium while she was accompanied by her husband. Nelly, a telephone operator was kept under constant verbal sexual abuse at work, and her anger exploded when she was grabbed by a strange man in the street.

The film eloquently illustrates the everyday-life-problems of women in Egypt at the eve of “the revolution” in 2011. Taking the film in point, the symposium explores the concept of “liberation” of its meanings and significances to the Egyptian society/ our everyday lives

【Program】

17:00 Opening remarks: IKEMOTO, Yukio (Tokyo University / Vice-Director, ASNET)

17:10 The First Session

Film screening “678”

Director Mohamed Diab

Arabic (Japanese Subtitle by Emi Goto) 90min, Egypt, 2011

18:50 Break (hot drinks will be served)

19:20 The Second Session

Moderator: GOTO Emi (Tokyo University)

Discussants: MATSUNAGA Noriko (Teikyo University)

MORIYAMA Noritaka (Tokyo University)

TORIYAMA Junko (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science)

19:50 Discussion

20:20 Closing Remarks

NAGASAWA Eiji (Tokyo University / Adviser, Middle Eastern Film(s) Study Group)

【Language】

Japanese

【Fees】

No charge

【Admission Capacity】

120

Admission will close when the prescribed number is reached.

【Organizer】

Network for Education and Research on Asia (ASNET), The University of Tokyo

Middle Eastern Film(s) Study Group

【Co-organizer】

The University of Tokyo

Research and Information Center For Asian Studies (RICAS)

Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia